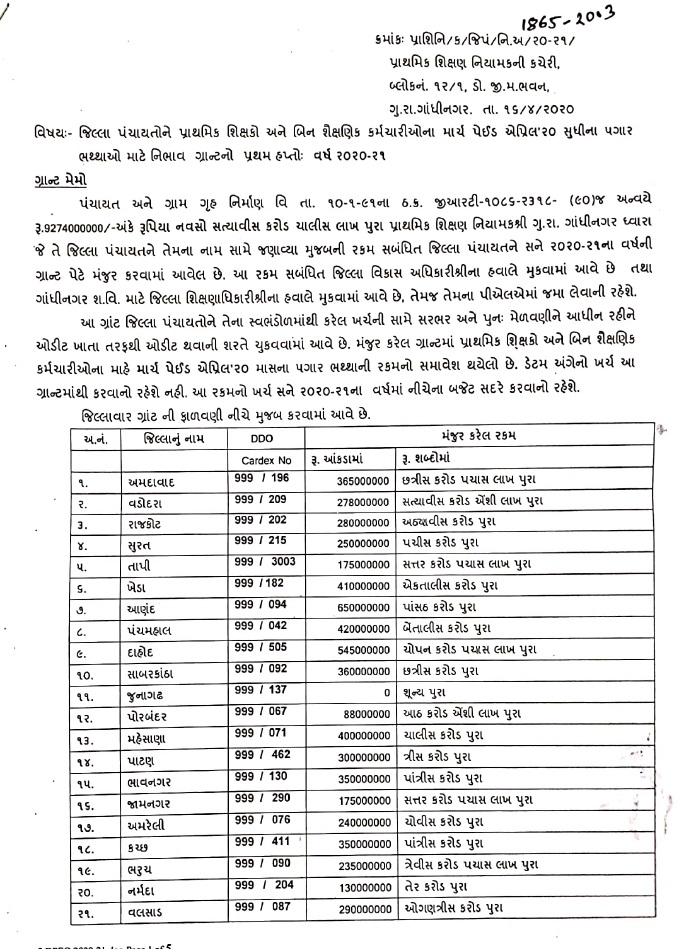

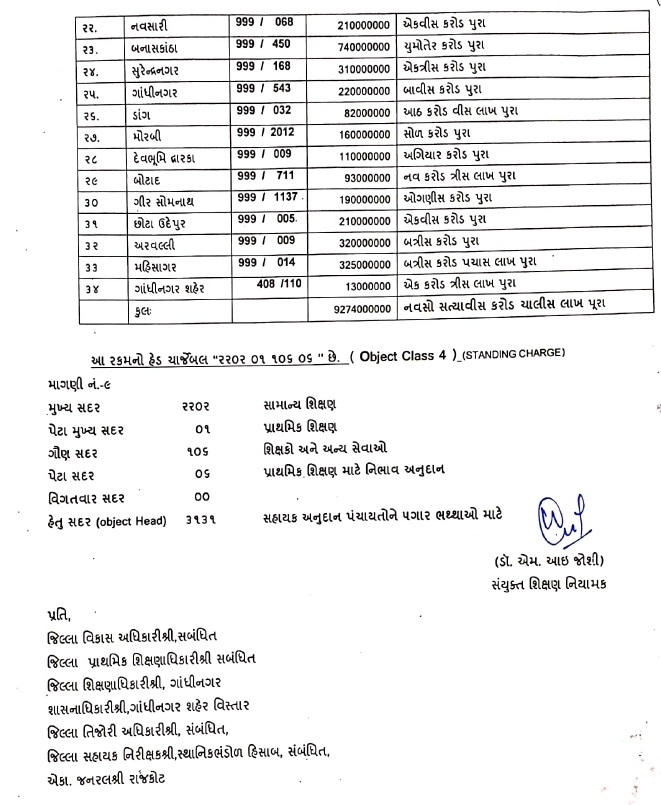

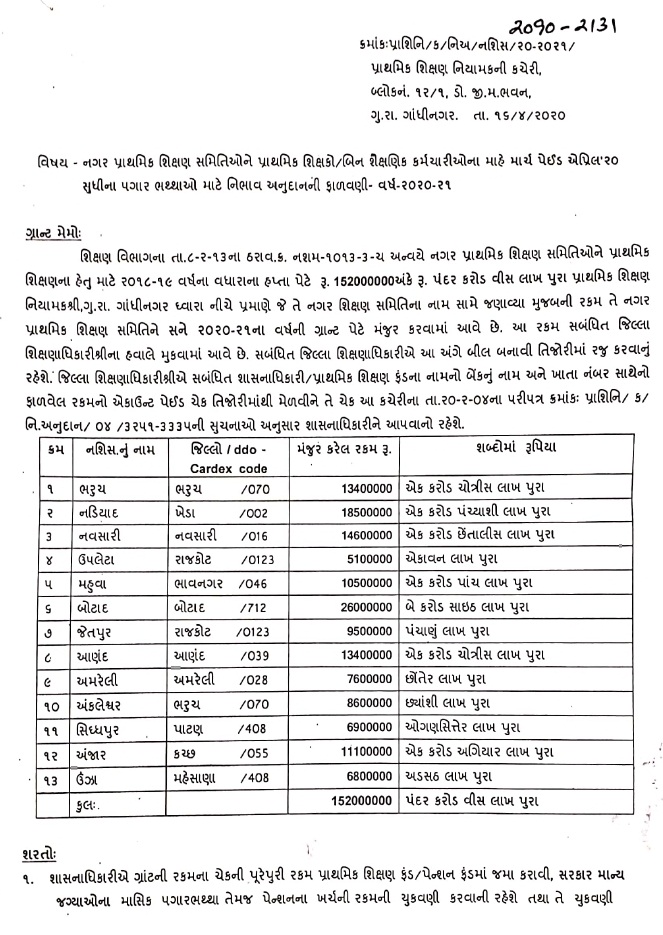

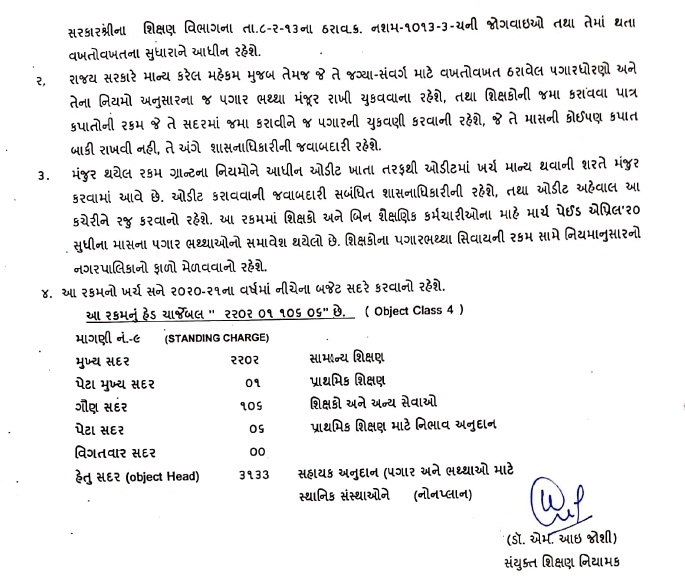

PRATHMIK SHIXAKO ANE BIN SHAIXANIK KARMACHARIONA MARCH PAID APRIL 2020 SUDHINA PAGAR BHATHTHAO MATE NIBHAV GRANTNO PRATHAM HAPTO VARSH 2020-21

There is a relatively simple fact about the Engelmann and Carnine theory that many educators appear to find

disturbing: it is the only theory of instruction and therefore, does not require the “direct” qualifier. Although we hear of

all kinds of “theories” of learning and even a few “theories” of instruction, this book represents the only theory of

instruction that would withstand the rigorous tests of theories required by philosophers of science—disciplined logical

interconnectedness, predictive value, parsimony, etc.

Theory of Instruction does not prescribe any “one best way,” but rather, describes a range of best ways, and

suggests an infinite range of ineffective ways. (If I were to set out to intentionally design the worst instruction possible,

I would still look to Theor

There is a relatively simple fact about the Engelmann and Carnine theory that many educators appear to find

disturbing: it is the only theory of instruction and therefore, does not require the “direct” qualifier. Although we hear of

all kinds of “theories” of learning and even a few “theories” of instruction, this book represents the only theory of

instruction that would withstand the rigorous tests of theories required by philosophers of science—disciplined logical

interconnectedness, predictive value, parsimony, etc.

Theory of Instruction does not prescribe any “one best way,” but rather, describes a range of best ways, and

suggests an infinite range of ineffective ways. (If I were to set out to intentionally design the worst instruction possible,

I would still look to Theor