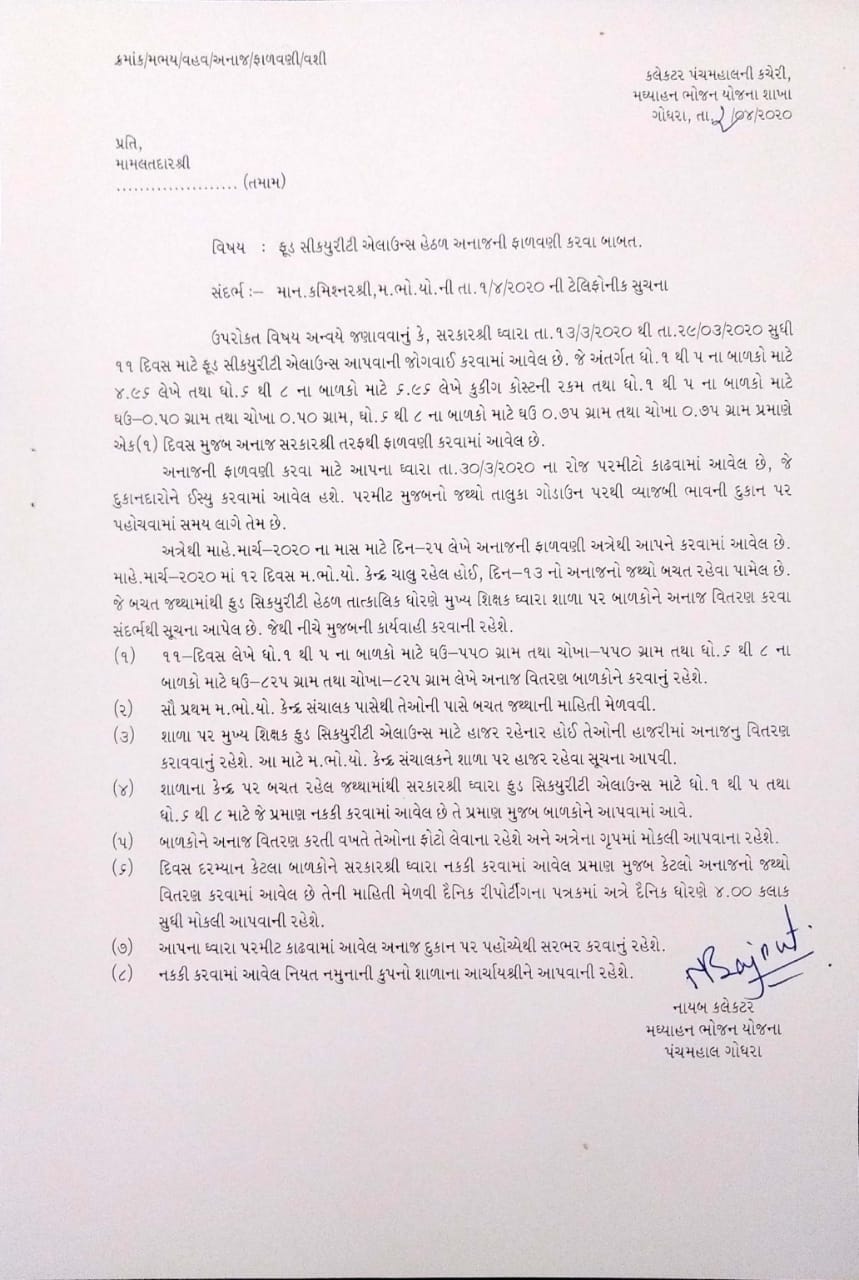

PANCHMAHAL:FOOD SECIRITY ALLOWNCE HETHAL ANAJ TATHA COOKING COSTNI RAKAMNI FALAVANI KARVA BABAT

Food security, as defined by the World Food Summit (WFS) and the Food and Agricultural Organization, ‘exists when all people at all times have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary and food preferences for an active life1’. Food security is also linked with a host of other factors, such as, socio-economic development, human rights and the environment. It has political ramifications as well. For instance, the price rise of various foods, such as onions and sugar, was a major issue during the general elections of 2014 in the capital. Therefore, a rise in food prices is bound to have consequences which cannot just be restricted to hunger and malnutrition, but it can also result in increasing health care expenditure and a greater economic burden on the citizens. Poor health and nutrition would also have an adverse impact on education, as children would be forced to stay away from schools. In fragile political and security situations, rising food prices can also trigger unrest and protest, and contribute to conflict.

The serious concerns related to food security in the developing countries have assumed global proportions in the last few years, with a need for urgent action. Henry Kissinger is reported to have declared, at the first World Food Summit, held in 1974, that in 10 years no child would suffer from malnutrition.2 He was, unfortunately, way off the mark in his prediction. The 1996 World Food Summit (WFS) in Rome had pledged ‘…to eradicate hunger in all countries, with an immediate view of reducing the number of undernourished people to half their present level no later than 2015.’3 Further, the first of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), established in the year 2000 by the UN, had included the target of ‘cutting by half the proportion of people who suffer from hunger by 2015.’ Progress towards meeting this MDG target (Target 1c) is assessed not only by measuring under-nourishment or hunger, but also by a second indicator, i.e. the prevalence of underweight children below the age of five.4

As regards the MDG 1c, the developing regions, as a whole, have almost reached the target. On the other hand, the Rome Declaration goal of 1996 has been missed by a large margin.5 The under-nourished population of the world, in 1990–1992, was about one billion. This had to be brought down to 515 million. However, as a substantial number of these persons were freed from hunger, the world population also grew, and the number of hungry people stood at 750 million in 2015.

There were also regional variations in the achievement of the MDG 1c across developing countries. In South Asia, progress has been too slow to meet the international hunger targets. India still has the second highest number of under-nourished people in the world, and has not reached the WFS or the MDG targets. However, on the bright side, higher world food prices, observed since the 2000s, have not entirely translated to higher domestic food prices, thanks to the extended food distribution programmes, though higher economic growth has also not been converted to higher food consumption. India’s food security issues date back many years to the time of colonial rule, and are complex, involving problems of production, distribution, storage and dietary mix. They have immense ramifications for the nation’s health indicators and economic development, which can also impinge on national security. This article attempts to briefly trace the genesis of the problem, outline the strategies undertaken by the Indian State to tackle it, highlight various issues related to food security that have figured in the recent public discourse and also explain the response of the State to address the present problems.

This article examines India’s efforts to achieve food security. It traces the problem, from the inadequate production of food grains during colonial times, to the challenges of procurement, storage and distribution of cereals in post-independence India, after achieving self-sufficiency in food production. The establishment of the Public Distribution System (PDS) and its evolution into the Targeted PDS and the National Food Security Act are outlined. The role of the Food Corporation of India and the efforts to improve it, are discussed. A critical analysis of India’s food security system is made in light of present day problems.

Food security, as defined by the World Food Summit (WFS) and the Food and Agricultural Organization, ‘exists when all people at all times have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary and food preferences for an active life1’. Food security is also linked with a host of other factors, such as, socio-economic development, human rights and the environment. It has political ramifications as well. For instance, the price rise of various foods, such as onions and sugar, was a major issue during the general elections of 2014 in the capital. Therefore, a rise in food prices is bound to have consequences which cannot just be restricted to hunger and malnutrition, but it can also result in increasing health care expenditure and a greater economic burden on the citizens. Poor health and nutrition would also have an adverse impact on education, as children would be forced to stay away from schools. In fragile political and security situations, rising food prices can also trigger unrest and protest, and contribute to conflict.

The serious concerns related to food security in the developing countries have assumed global proportions in the last few years, with a need for urgent action. Henry Kissinger is reported to have declared, at the first World Food Summit, held in 1974, that in 10 years no child would suffer from malnutrition.2 He was, unfortunately, way off the mark in his prediction. The 1996 World Food Summit (WFS) in Rome had pledged ‘…to eradicate hunger in all countries, with an immediate view of reducing the number of undernourished people to half their present level no later than 2015.’3 Further, the first of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), established in the year 2000 by the UN, had included the target of ‘cutting by half the proportion of people who suffer from hunger by 2015.’ Progress towards meeting this MDG target (Target 1c) is assessed not only by measuring under-nourishment or hunger, but also by a second indicator, i.e. the prevalence of underweight children below the age of five.4

As regards the MDG 1c, the developing regions, as a whole, have almost reached the target. On the other hand, the Rome Declaration goal of 1996 has been missed by a large margin.5 The under-nourished population of the world, in 1990–1992, was about one billion. This had to be brought down to 515 million. However, as a substantial number of these persons were freed from hunger, the world population also grew, and the number of hungry people stood at 750 million in 2015.

There were also regional variations in the achievement of the MDG 1c across developing countries. In South Asia, progress has been too slow to meet the international hunger targets. India still has the second highest number of under-nourished people in the world, and has not reached the WFS or the MDG targets. However, on the bright side, higher world food prices, observed since the 2000s, have not entirely translated to higher domestic food prices, thanks to the extended food distribution programmes, though higher economic growth has also not been converted to higher food consumption. India’s food security issues date back many years to the time of colonial rule, and are complex, involving problems of production, distribution, storage and dietary mix. They have immense ramifications for the nation’s health indicators and economic development, which can also impinge on national security. This article attempts to briefly trace the genesis of the problem, outline the strategies undertaken by the Indian State to tackle it, highlight various issues related to food security that have figured in the recent public discourse and also explain the response of the State to address the present problems.

This article examines India’s efforts to achieve food security. It traces the problem, from the inadequate production of food grains during colonial times, to the challenges of procurement, storage and distribution of cereals in post-independence India, after achieving self-sufficiency in food production. The establishment of the Public Distribution System (PDS) and its evolution into the Targeted PDS and the National Food Security Act are outlined. The role of the Food Corporation of India and the efforts to improve it, are discussed. A critical analysis of India’s food security system is made in light of present day problems.

No comments:

Write comments